The couturier’s huge collection of modern art, 18th-century furniture and decorative objects is the subject of a landmark three-part auction at Christie’s Paris

‘Les projets. Toujours les projets,’ was the principle by which

Hubert de Givenchy organised his work, his homes and his life. Charles Cator,

now Deputy Chairman of Christie’s International, recalls arriving at the

couturier’s Parisian home in the summer of 1993 to spend two weeks cataloguing his

collection of 18th-century furniture for an auction later that year. Givenchy

would repeat those words again and again.

‘Visual flair is useful, but it is not enough,’ says Cator. ‘The greatest and most skilled collectors are curious, with a compulsion to

understand what they are acquiring. Their collections, their homes and their

lives become a kind of perpetual gesamtkunstwerk — a physical

catalogue of mental preoccupations, diversions and creative stimuli. Think of

the collections of Peggy Guggenheim, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis or David Bowie

— a shared approach that is the opposite of assembling a showroom. Givenchy’s

tastes were nothing like theirs, but his approach was the same. We can learn

much from him.’

Givenchy — or ‘Le Grand Hubert’ as he was known

among the fashion cognoscenti, an affectionate reference to his 6ft 6in stature

— was one of the greatest couturiers of the 20th century. But beyond fashion

he was a ceaseless collector of art and antiques, and spent years restoring and

decorating his grand houses. His taste was rigorous, eclectic and restrained,

as if a lifetime dedicated only to couture would never be enough for his

intellect and eye.

‘I like to describe it as a reaction like a

camera lens,’ says Cator, who became a long-time friend and colleague of the

designer. ‘His ability to zoom in on that one detail, and place it in a larger

space. It was a knack he had.’

Givenchy’s collection will be auctioned with live sales at Christie’s Paris on 14 and 15-17 June, accompanied by an online sale from 8-23 June. Hubert de Givenchy — Collectionneur features more than 1,200 lots drawn from two of Givenchy’s homes: the Hôtel d’Orrouer on the Left Bank in Paris and the Château du Jonchet in the Loire Valley.

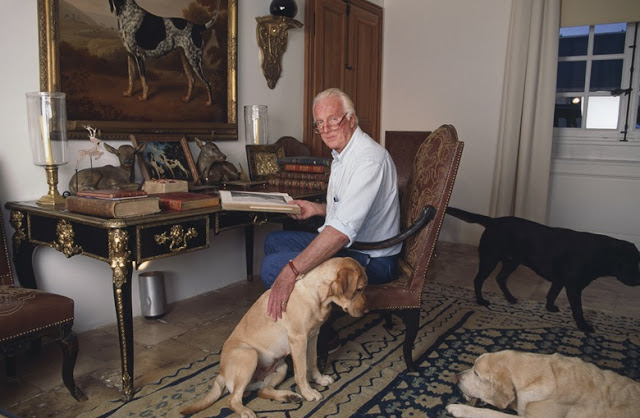

Hubert de Givenchy

and his beloved dogs at his home, the Château du Jonchet, October 1995. Photo:

Getty Image

Hubert James Taffin de Givenchy, who died in 2018 aged 91,

undoubtedly had a head start in life — he was a French-Venetian aristocrat and

the youngest son of a marquis. His instinct for fine textiles came early on:

Jules Badin, his maternal grandfather, was the director of the Beauvais and

Gobelins tapestry factories.

Givenchy’s mother, Béatrice, wanted him to be a lawyer. When, aged

17, he told her he would prefer to study at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris,

she relented, telling him to do so if he must, only to do it well.

Eight years later, in 1952, he opened Maison de Givenchy, which he

swiftly established as one of the most progressive couture houses of the

post-war era alongside contemporaries such as Christian Dior and Pierre Balmain.

His lengthy list of famous clients included the film stars Audrey Hepburn and

Grace Kelly, as well as the Duchess of Windsor and Jackie Kennedy Onassis. He

would lead Maison de Givenchy for 43 years until his retirement in 1995.

Throughout these decades, working with his life partner Philippe

Venet (1929-2021), Givenchy bought, renovated and remodelled several historic

properties. Gardens were planned and laid out, and thousands of pieces of

furniture, paintings and objects were acquired and displayed. Givenchy even

commissioned paintings of the interiors he had created.

As a collector he had wide-ranging tastes. His favourite fine art

was from the 20th century — Miró, Picasso, Rothko, Alberto and Diego Giacometti —

but he also loved 18th-century furniture and the decorative arts. He saw no

reason for them to be displayed separately, so modern art was mixed with the

decorative, and ornament was no crime.

In 1975 Givenchy commissioned Diego (1902-85) — Alberto’s younger

brother and himself an accomplished designer and sculptor — to make a door knocker in

patinated bronze for his home. It would be the first work of art his visitors

would encounter when arriving at the front door.

The rose garden at Le Jonchet was designed by his lifelong friend

and confidante Rachel Lambert ‘Bunny’ Mellon (1910-2014), the American

horticulturist and collector whose design motto was ‘nothing should be noticed’

— by which she meant that design was about composition, not individual

components. Each work should therefore occupy its place while quietly speaking

of its quality, but at the same time remaining discreet.

Mellon also designed Jackie Kennedy’s rose garden at the White

House in Washington, DC, since remodelled - somewhat controversially - under

the instructions of Melania Trump. Givenchy and Mellon’s shared taste ran deep:

her staff even wore uniforms designed by his atelier. They were so close that

she had her own room at his seaside home, Le Clos Fiorentina in Cap Ferrat, and

at Le Jonchet, as did he at her estate in the US.

Mellon informed the designer’s taste, introduced him to artists,

and was instrumental in his acquisition in the 1970s of one of the highlights

of the 14 June Paris auction: Alberto Giacometti’s bronze Femme qui marche,

cast in 1955. Both collectors were friends of the great post-war sculptor,

whose ability to reduce the human form to its core characteristics caught

Givenchy’s eye again and again.

This was a period when he was rapidly expanding his collection, and

which coincided with the height of his creative powers. The Miró is hung near

an ornate Boulle cabinet, adjacent to modernist sofas and a table stacked with

books — a typical Givenchy interior. The painting also hung in his bedroom and

was the last work of art he saw at night and the first in the morning.

Für Tilly (1923), a colourful geometrical abstract by

Schwitters, is less ethereal than the Miró. It was acquired by Givenchy at about

the same time, as was the Picasso, Faune à la lance (1947), a drawing in black

chalk of a smiling, seated horned figure.

Givenchy did not just collect modern art, as is clear from a pair

of 18th-century ormolu stags, once owned by the Rothschild family and acquired

by Givenchy at Christie’s in 2006. Stags were emblematic for the couturier: a

row of sculpted stag heads by Alban Reybaz adorned the main façade at Jonchet,

and a near-life-size bronze sculpture by François Pompon (1855-1933), once an

assistant to Rodin, sat in one of its salons. St Hubert is, of course, the

patron saint of hunters - a slight irony, as Hubert was not a hunter but rather

a lover of all creatures great and small.

He was also devoted to his many dogs, and commissioned Diego

Giacometti to make small sculptures of his favourites to mark their graves. Several of these bronzes are included in the day sale.

Givenchy’s greatest joy, however, was

18th-century furniture. There are about 440 chairs, as well as wonderful pieces

by some of the most famous ébénistes and furniture makers of the time to be

found in the sales. He would often choose the upholstery for the pieces he

acquired, as he did with six rare Louis XV chairs by Claude Sené I, made in

1743. Givenchy commissioned their leather and suede upholstery with applied

acanthus-leaf motif from his very own glove-makers. Charles Cator spoke of the

fact that every piece of furniture carries a little of its past owner with it

when it moves to a different collection. Here we see that in the literal sense, which is quite remarkable

and rather unique.

Similarly, he had a pair of elegant, scroll-back cream-painted

chauffeuses, made by Georges Jacob in

1785, upholstered in dark green velvet, his favourite colour, and a Louis XVI

gilt and giltwood bergère upholstered in maison Le Manach tiger-print velvet -

an example of Givenchy’s playful taste.

For Cator, the summer he spent working with Givenchy’s collections

nearly 40 years ago was transformative. ‘He changed my working life,’ he says.

‘He was an incredibly generous figure.’ Photographs of the rooms he designed

and the objects he collected throughout his life reflect his pursuit of order,

and his thirst for visual stimulation. He was fearless in his pursuit, says

Cator. ‘Givenchy was uninterested in “bargains” and unafraid to pay the right

price. He eschewed trends and investments. He preferred to "put things

together and live with them".'

https://www.christies.com/features/great-taste-never-goes-out-of-fashion--the-eclectic-vision-of-hubert-de-givenchy-12290-1.aspx?sc_lang=en&cid=EM_EMLcontent04144C11Section_A_Story_1_0&COSID=42665747&cid=DM478597&bid=313503109#fid-12290

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario