Mary Beard photographed in Cambridge by Amit

Lennon for the Observer.

The Cambridge classicist on owning her TV

image, dealing with internet trolls, and why her new book on Roman emperors

sheds light on our preoccupation with statues

Rachel Cooke

@msrachelcooke

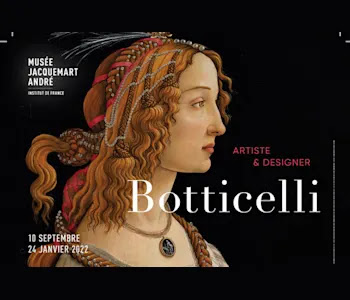

In her new book, Twelve Caesars, Mary Beard

touches enticingly on the life of Elagabalus, a man whose excesses seemingly

outstripped even those of Caligula or Nero. Elagabalus, also known as

Heliogabalus, was only briefly emperor of Rome – he was assassinated by the

Praetorian Guard when he was still a teenager – but he has a special place in

Beard’s head, if not her heart. Should a journalist casually inquire which

emperor some modern-day politician might bring to mind, his is the name she

often gives in reply. Beard likes to unsettle those in search of lazy analogies

and hardly anyone, she says, has heard of this bloke. Even better, she can then

send the baffled and the bemused to Roses of Heliogabalus, a painting of 1888

by Lawrence Alma-Tadema that depicts the emperor’s party trick, which was to

smother his guests to death beneath piles of rose petals. “Once you know that

story, you understand tyranny much better,” she says, with predictable relish.

“There is no safe point. Even the generosity of emperors could be lethal.”

To be frank, I hadn’t heard of Elagabalus

either, or not before I read her book, and the same, alas, goes for almost

everyone else in it. But to my amazement, this hardly mattered. Twelve Caesars

is fascinating and not only because its author writes so engagingly. Many years

in the making, the world into which it will be born is not quite the same as

the one in which it was conceived. Its preoccupations – essentially, it’s about

the way that images of Roman emperors from Caesar to Domitian have influenced culture

across the centuries – are suddenly and newly of the moment in a Britain that

has become completely fixated with statues.

In the garden of her Cambridge home, Beard

blinks in the late summer sunshine. Famously, she isn’t convinced that Rhodes

should fall (Cecil Rhodes, the colonialist whose statue students at Oxford

University have campaigned to have removed from Oriel College on the grounds of

his racism). However, this isn’t for her a point of principle, to be applied to

all statues, everywhere. “I’m very happy that some statues come down,” she

says. “They always have. They always will. The idea that nothing can ever be

moved is mad. What I am suspicious of is the thought that the only function

they fulfil is to be admired. The book points to bigger questions about images

of power. A statue may also tell us how not to be. It may tell us what

a monarch isn’t, as well as what he is. They’re part of a debate.”

The meaning of a statue, moreover, may shift

and then shift again. At Chatsworth House in Derbyshire, for instance, there is

a sculpture by Antonio Canova of Napoleon’s mother, Letizia Bonaparte,

commissioned by its subject in 1804 (it was sold to Chatsworth’s owner, the

Duke of Devonshire, after Napoleon’s fall). Canova based it on a classical statue

of a woman who at the time was widely (and, it turns out, wrongly) identified

as Agrippina. But which one? Agrippina, the virtuous granddaughter of Augustus

and wife of the admired Germanicus? Or Agrippina, the villainous wife of

Claudius, whom she poisoned, and the mother – and possibly lover – of the

dreaded Nero? As Beard relates, an alignment with either would have had political

implications for Madame Mere (as Napoleon’s mother was known) and thus for her

son too. Once installed at Chatsworth, however, all insinuations were promptly

lost. A once controversial work of art – a piece that asked awkward questions

about imperial power and dynasty – was, and is, merely an accomplished portrait

by a famous artist. Its marble curves and folds may be exquisite, but they’re

also a little bit bland, denuded of all deeper significance.

Why does she think that Roman emperors, images of whom appear

everywhere from Renaissance paintings to Carry On films, ancient coins to the

comic book adventures of Asterix, exerted (and still exert) such a hold on

human beings, whether subjects, citizens or rulers? Or is this a stupid

question? She shakes her head. “There’s no simple answer to that. Partly, it’s

historical. The monarchs of early medieval Europe decided they were going to be

the continuators of the emperors and it went from there. It was a way [for

rulers] to talk about power, but at a safe distance. How much easier talking

about the emperors than about the tyranny of your great-great-grandfather 200

years ago.

“But there’s also Suetonius [the Roman historian who first gave us

the category of the 12 Caesars and who might be described as the presiding

spirit of her book]. He was very helpful. All those trivial, gossipy details.

If you say someone killed 95 members of the Senate, it’s hard to see it. But if

you say he slaughtered flies with his pen nib [something Domitian was supposed

to have done], it’s graspable. It’s like the rose petals: picture them and

you’re right there, at that dinner.”

In a social media pile-on, you’re being

pummelled. You’re getting punched. It’s a communal assault

Beard lives in a big Victorian house a taxi

ride from the centre of Cambridge with her husband, a historian of Byzantine

art. It sits between two tunnels. The first, leading to the front door, is

formed of wisteria. The second is built of shelves, books and glass – OK, it’s

more of a corridor than a tunnel – and connects the house to her study here in

the garden. This space is a great luxury, she tells me: once she’s safely

inside it, interruptions are less likely. But she makes light of her workload,

for all that I detect Stakhanovite impulses. When we discuss the lectures on

which her book is based (they were delivered in Washington DC in 2011), she’s

happy to admit that once she’d decided on a subject, she didn’t think about

them again for a year and it was only once she began writing them that her

ideas began to form. In another life, it occurs to me, she might have made a

good journalist.

But perhaps another life is just around the

corner. Beard, a professor

of classics at Cambridge, will retire next year, after more than four decades

at the university. What does she plan to do? More television? (Another series

of her BBC Two show, Inside Culture, begins on 24 September.) “Yes,” she says.

“But you have to be realistic. Telly will get fed up with me at some point.”

Nevertheless, she will stick with it for as long as she can. In her view, it

can only be a good thing that she is on screen: “Being an older woman who is

uncompromisingly an older woman… People might say things haven’t changed [for

older women]; that, you know, they just use a few eccentrics like Beard as

window dressing. But it makes a difference for girls to see a range of

different women.”

Was there ever a moment when she thought about

just giving in and getting a new wardrobe and some Botox? (She began her TV

career in 2010 at the behest of Janice Hadlow, then controller of BBC Two,

who’d read her Pompeii book on holiday.) “I think if I’d gone into it earlier,

I probably would have done that. But there comes a point where you think: I

can’t look the part. Don’t humiliate yourself by trying to look the part! At

least it’s me that I see on the telly. I sort of own it, sometimes for better and sometimes for worse.”

Mary Beard at the Museum of Classical Archaeology in Cambridge for

her TV show Shock of the Nude. Photograph: Polly Alderton/BBC/Lion Television

Ltd

But there has, of course, been a downside to this determination to

be herself. Since fame arrived, Beard has had to endure some of the vilest

attacks on social media I’ve ever seen. How does she remain so smiling and

seemingly sane in the face of such onslaughts? “By being bloody minded,” she

says. “Training yourself to say: I’ve got a thick skin, nothing can hurt me.”

It’s not easy, though, even now. “When you get a real pile-on… You know what

you should do. You see the tweets coming in, abusing you every 10 seconds. You

know you should just turn it off. But it’s impossible. You’re being pummelled. You’re getting punched. It’s a communal assault,

but those doing it are also individuals. You’re very close to losing it.”

Her attitude to internet trolls – in 2013, she

befriended one of hers, going out for lunch with him and later writing him a

reference – is not unlike her attitude to tyrants, which involves a certain

amount of (possibly rather daring) empathy. “It’s unfashionable to be

sympathetic to a monarch,” she says. “But it must be one of the most terrifying

things in the world: bed-wettingly scary. You’re the one person who knows

you’re a flawed human being… that you’re just a guy.”

Most people can’t go to the Louvre. Maybe we

should take the great works of art to the people

During the pandemic, Beard presented Inside

Culture from her home. She was glad to do it. She felt it was important. But

she also thinks now that the arts world resorted in this period to an argument

she doesn’t much favour when it comes to the question of funding. “The arts make us

feel better, people said – and I’m sure they do. But I also think this is a dangerous line to follow. The real reason we

needed the arts was because we needed to understand what we were going through.

I’m not going to sit here and say, what do we need more: a vaccine or the arts?

That’s a false equivalence. But crises are recovered from by people learning about them. What

did we feel and why? If we want to look at plagues and pandemics, well, western

literature in the form of The Iliad starts with a plague! The arts are essential and that’s what we must fight for.”

Two things, though, are happening at once:

push and pull. As the government ponders retrenchment, elsewhere a correction

is taking place, particularly in our museums. The emphasis of collections is

changing, politically speaking, and commitments are being made to return

objects to their first homes. “That could be equally dangerous, if it’s not

done at a measured pace,” she says. “Speed, kneejerk reactions. I think they’re

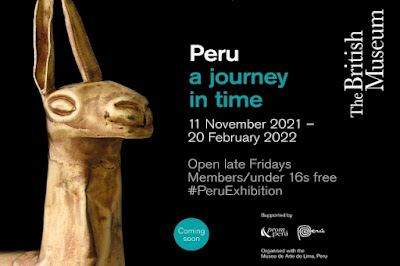

a problem.” Beard, who is a trustee of the British Museum, would like such

debates to be seen in terms of something bigger. “You understand the

investment, the sorrow and pain [at the thought of beloved objects departing].

But what will museums be for in 50 years? We might think about moving objects

around more than people. It may be better to put a load of them on a plane than

a load of us. Most people can’t go to the Louvre. That’s a very privileged

thing to do. Maybe we should take the great works of art to the people.”

What about her students? How has the pandemic

affected them? “I feel sad for them,” she says. “University is about talking to

people late at night over a bit too much to drink. It’s easy to take the piss:

oh, they’re just missing the parties. But that’s what they’re supposed to be

doing.” She taught virtually, painfully aware that this was easier for students

she already knew (it was the freshers who really suffered). What about the mood

otherwise? We read so much about no platforming and cancel culture. “It’s

hugely exaggerated. But it’s not an entire invention.” She has heard of

students who are unwilling to read Ovid’s Metamorphoses on the grounds that it

is a poem of rape. “When I was taught it in the 70s, it was about ravishment,

not rape. The sexual violence was whited over. Later generations have seen it

and that’s important. But I will argue until the cows come home that

it should be read. Ovid is much too clever a poet not to problematise rape.”

She feels similarly about trans rights: that

there are things that must be talked about, however difficult. Newnham College,

where she was an undergraduate and is now a fellow, is women only. “As far as I’m

concerned, my students are who they say they are. If they say they’re a woman,

they’re a woman. But all this then gets confused with something that most of us

don’t spend time thinking about, which is the philosophy of sex and gender.

Like a lot of high theory, it doesn’t make a difference to my day-to-day life.

It’s perfectly possible to deplore what happens to some trans people, but also

to feel that there is a philosophical debate to be had.” Biological sex exists,

she says – and yes, old-fashioned misogyny is abroad once again: women being

called “witches” and so on. “It’s a terrible zero-sum game. I feel sad

really. Nice people are getting hurt on both sides. But if you’re an academic,

you have to say that there are things that must be talked about.”

It strikes her now that the feminism of her

younger self was perhaps naive. “I thought that as long as you provided

nurseries, childcare, contraception, abortion and equal pay, that we would be

done. But, no.” Even if we had all these things, which we don’t, we’d still be

fighting for our rights: “It’s what goes on in heads that counts. The learned

assumptions are still there.” In Shrewsbury, where she grew up, feminism was

mostly notional for her; reading Simone de Beauvoir and Germaine Greer as a

teenager was intellectually exciting, but such books seemed to have no

practical applications. Her mother, a primary school head, had not been to

university and wanted her daughter to have the opportunities she had not: “I

didn’t think there were people who would say engineering isn’t for women.”

But then she went out into the world and there

it was: sexism. There was a period, once she was teaching at Cambridge when she

was the only woman in her faculty. “Such a situation can completely marginalise

you, but it put iron in my soul. I felt confident about dealing with these

guys. I’d babysat for some of them [as an undergraduate]. I developed a load of

rhetorical tricks, like calling them ‘boys’ after they’d gone on and on. ‘Oh,

for crying out loud, boys!’ I’d say. I could fight back.

“But one’s feeling of exclusion is an aggregate of trivial things.

It’s not that someone sits there and says: you’re not welcome, dear. We’d have

meetings and there would be a coffee tray. The meeting would end and the boys would

walk out. It would be left to me and the secretary to clear the cups.

Eventually, I started saying [pointedly], ‘Could someone take a tray, please?’”

She found solidarity with other women too. As a graduate student, she belonged to a consciousness-raising group. “Yes,

we all bought specula [she says the word as only a classicist can] so we could

all sit down and find our cervix with a mirror.”

Will she miss university life? It seems to me

to have made her, in big ways, as well as in smaller ones. “It is a big

change,” she agrees. “I’ll be 67 and the question is: will I get 10 good years

or 15? It’s all downhill after this. You’re looking death in the eye. As a

friend of mine said, the illnesses you get after 60 are likely to be the ones

that kill you. But I am looking forward to it and it’s important to make way

for younger people.” Is she the academic equivalent of a bed-blocker? She

laughs. “Well, I’ve had my go. I’ve enjoyed it, but there are other things I

can do.”

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/sep/19/mary-beard-twelve-caesars-interview