Since about the 1970s, a new and largely post-vernacular Yiddish

culture has started to develop in many, often unexpected, locales around the

world. A related visual aesthetic now seems to be emerging.

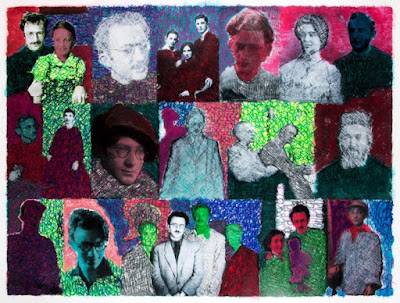

Yevgeniy Fiks

Shterna Goldbloom,

“Feygele” (2018) from the “Feygele” project (image courtesy the artist)

Since about the 1970s, a new and largely, what the historian

Jeffrey Shandler terms, a “post-vernacular Yiddish culture” has started to

develop in many, often unexpected, locales around the world. This phenomenon

exists in parallel to and as a continuation of the surviving secular Yiddish

culture that descended from pre-War culturati circles of Vilnius, Warsaw,

Moscow, New York, and elsewhere.

This new Yiddish culture was created by a post-World War II

generation of Jewish and non-Jewish artists and academics who (re)discovered

and (re)learned the Yiddish language and employed it for cultural production —

mostly music, theater, and literature — as the medium and the message. It came into maturity in the era of identity politics in the 1990s and

2000s. The avant-garde of this culture is post-modern, hybrid, progressive,

humanist, and intersectional. This new Yiddish culture welcomes contemporary

subjects and forms formerly considered taboo (e.g. non-heteronormative gender

and sexuality) while maintaining the long-standing commitment of the

historically secular Yiddish culture to equality and social justice. This

intersectionality opened up spaces for queer yiddishkeit, such as the

African-American Yiddish work of Anthony Russell which combines African American

spirituals and the music of Jewish Eastern Europe, and the staging of “Waiting

for Godot” in Yiddish in New York by the New Yiddish Rep in 2013, among many

other examples.

The new Yiddish culture has evolved from the

tribal culture of the tight-knit Eastern European Jewish community and their

descendants, to an open culture, welcoming creators from different backgrounds

and paths in life and working with multitudes of subjects and forms.

While art forms that directly employ language

— literature, music, and theater — naturally became primary forms of the new

Yiddish culture, Yiddish contemporary (visual) art has yet to emerge. But what

would constitute Yiddish contemporary visual art? How would we recognize it? Is

it contemporary visual art that uses the Yiddish language in some form — as

text, letterforms, speech — for example, a video or sound installation or a

performance art piece? To what extent and in what forms must the Yiddish

language must be present in an art piece to be considered Yiddish contemporary

art? Perhaps “Yiddish contemporary art” needs to be defined in more open-ended

terms?

I propose we consider “Yiddish contemporary

(visual) art” as any contemporary art piece — contemporary painting, works on

paper, installation, photography, video, sound, performance art, new media,

social practice, etc. — that are consciously produced by the artist as a

project of this new Yiddish culture. This art can either directly employ the

Yiddish language, form, subjects, themes of Yiddish/Eastern European Jewish

culture or be situated in less straightforward relation to them. Works of

Yiddish contemporary art have an intentional and knowable connection to the

languages and cultures of Eastern European Jewish communities, in dialogue with

languages and cultures of their neighbors and the world at large.

The Chicago-based artist Shterna Goldbloom maps the difficulties

and complexities of bridging her Jewish and LGBTQIA identities. Her work

focuses on the experiences of queer Jews coming from traditional Orthodox

communities who had to negotiate or are still negotiating their sexual

orientation and gender identity within the tenets and practices of Haredi

Judaism.

Shterna Goldbloom,

“Feygele” (2018) image of the Dorner Prize Installation, RISD Museum

(photograph courtesy the artist)

Goldbloom’s project Feygeles uses the Yiddish slur for “gays” as

its title, which literally means a “little bird.” According to Goldbloom, the

title “expresses both the queerness of these Jews and their “flight” from the

communities they had to leave to accept and realize their sexual gender

identities and to their new communities of choice. Feygeles “aims to make

visible that which has historically been hidden” because queer Jews have always

existed and yet traditional Jewish communities refuse to acknowledge that

history or the presence of queer Jews in their communities today.

The contemporary Torah scrolls in the Feygeles installation are

handmade and include photographs of and interviews with queer ex-Orthodox and

Orthodox Jews “who have struggled to find ways of integrating their history and

family traditions with their sexuality and gender.” Each scroll is unrolled to a different degree, mirroring the different

levels of openness of the subjects’ identities. The photographs of the subjects

who are not openly LGBTQIA are kept shielded and concealed in closed Torah

scrolls. Some portraits are shown partially, while others are fully and proudly

displayed.

Contemporary Berlin-based artists Arndt Beck

and Ella Ponizovsky-Bergelson’s two-person exhibition “Di farbloyte feder |

Berliner zeydes,” held last summer at the ZeitZone Gallery in Berlin is an

example of such contemporary Yiddishist art practices.

Ella Ponizovsky Bergelson, “My Paper Bridge”

(2019) (courtesy the artist, photo by Arndt Beck)

Ella Ponizovsky-Bergelson, who was born in

Moscow and grew up in Israel, works in hybrid calligraphy and is interested in

“what happens to words and sentences when you change the language or the

alphabet” as in her “Among Refugees Generation Y,” a piece of calligraphy on a

wall in the Neukölln district of Berlin where Yiddish, Arabic, and German

languages pervade.

Ponizovsky-Bergelson’s work in “Di farbloyte

feder | Berliner zeydes” is based on the Yiddish poem “A papirene brik” (“My

Paper Bridge”) by Kadya Molodowsky (1894–1975) who emigrated from Poland to the

United States in 1935. In this house-paint-on-a-wall piece,

Ponizovsky-Bergelson renders Molodowsky’s text in ancient Hebrew script in

vibrant primary colors, a radical gesture given the standard monochromatism of

post-Holocaust Jewish-themed art that addresses the destruction of the

Ashkenazi civilization in Europe.

According to Ponizovskiy-Bergelson in an

interview with Ekaterina Kuznetsova in Geveb: A Journal of Yiddish Studies: “If

we are bringing Yiddish back to life, to the present and the future, it is

better to do it in color to break the stigma and to get rid of this very sad

and tragic black and white picture.” Painting/writing the poetic text of

Molodowsky (who wasn’t religious), using ancient Hebrew script that evokes the

dawn of Judaism is a statement about the 20th-century, Eastern-European Jewish

trauma that suddenly rendered the once lively and vibrant early-20th-century

Yiddish secularism antiquated and exhausted.

The work by Arndt Beck, who was born in Berlin

in 1973, in “Di farbloyte feder | Berliner zeydes,” combines images from

documentary photos of early-20th-century, European-Jewish life with Yiddish

text, both rendered in decisively vibrant colors. As in the case of Ponizovsky-Bergelson’s

work, the use of color in Beck’s work violently clash with or subvert the

pre-conceptions of a sense of loss being appropriately conveyed by grayscale

imagery, a typical trope of early-20th-century documentary photographs

depicting pre-Holocaust Jewish life.

Beck’s works propose another type of

remembrance: an exuberant and carnivalesque one that can ensure the

continuation of Yiddish culture in new and existing, yet unexpected forms. The

Yiddish text in Beck’s works comes from Yiddish poems by Moyshe Kulbak

(1896–1937) and Avrom Sutskever (1913–2010) connected to Berlin and Yiddish

literary history in the city. Some of these poems have never been translated

fromYiddish until Beck engaged them in his artwork. This includes Sutskever’s “Brandenburger

tor” (“The Brandenburg Gate”) or his diary documenting his journey to the

Nuremberg Trials in 1945–46. Beck’s contemporary art practice is, in fact, part

of his multi-faceted Yiddishist culture work, where he acts as an organizer,

translator, and creator for the course of Yiddish.

Arndt Beck, “Berliner Grandfather” (2019)

(image courtesy the artist)

Canadian artist and researcher Avia Moore is a

Yiddishist who is a maker, producer, scholar, and dance leader. Moore’s

practice is performance and Yiddish dance and movement, but she often

collaborates on research projects, films, documentaries. Her performative,

research-based practice and its rootedness in the Yiddish text is exemplified

in her ongoing project “Letter Angel,” which began in 2006 based on a drawing

by Sarah Horowitz and an image of a girl navigating her way through the

aleph-beys (Yiddish alphabet) as a metaphor of a journey into Yiddish culture. This project mainly

consists of performative explorations, sometimes documented in photo and video

projects. “Letter Angel” was also explored through image, prop-making, text,

and music in trace, including Moore’s solo work (from movement explorations to

photography, to crafting) and ensemble work (movement, music, writing,

photography), also art books. According to Moore, “Letter Angel” is at bottom

about how we carry our “identities on our bodies” and “on our skin.”

Avia Moore, “A

malekh veynt” (2009); The wings are formed from the lyrics of a Yiddish song by

Peretz Hirshbein: “A malekh veynt” (an angel weeps) (courtesy the artist).

The forms of Yiddish contemporary art are

linked to forms representing the life of Yiddish culture today. They are of

various degree of religiosity, assimilation, connection to “the old home”, and

political commitment.

Yiddish contemporary art is not about reviving or resuscitating the

culture of the past but about continuing and reimagining Yiddish culture in

earlier unforeseen forms under new conditions.

At the same time, Yiddish contemporary art is

against forcing Yiddish culture into contemporaneity through a violent

modernization. Yiddish culture is a living culture that doesn’t need to be

“upgraded” to the imperialist standards of contemporary hegemonic cultures.

There is no need to translate forms and themes of hegemonic cultures into

Yiddish or to find Yiddish equivalents to them.

Yiddish contemporary art must be allowed to

develop under its internal logic. We do not need “Yiddish abstract expressionism”

or “Yiddish relational esthetics.” What we need are, simply, forms of Yiddish

contemporary art.

Forms of Yiddish contemporary art are both

already here and have yet to be developed. While rejecting the dictates of

cultural imperialism, Yiddish contemporary art is at the same time open to

everything progressive locally and globally.

It strives for the equilibrium between

particularism and universalism. It is migrant, diasporic, and global. It is

representational, modernist, monumental, ephemeral, participatory, and

performative.

The colors of Yiddish contemporary art are

exquisite, its forms are refined, and its lines are trembling.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this article left out analysis

of the artist Shterna Goldbloom. It has now been updated to include her.

https://hyperallergic.com/581286/is-there-a-new-yiddish-contemporary-visual-art/?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=D081320&utm_content=D081320+CID_e2598f232fce2296beba234dcd766a4d&utm_source=HyperallergicNewsletter

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario