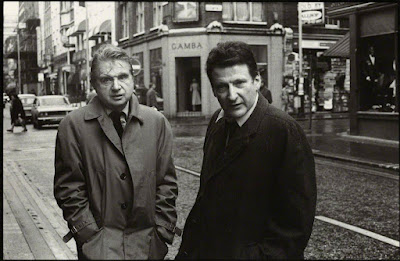

The three visionary artists, represented in the collection of Paul G. Allen, all emerged in post-war London but revolutionized different ways of seeing and painting the figure

In the aftermath of the Second World War,

London was a city of rubble. More than 100,000 buildings had been destroyed, or damaged beyond

repair by enemy bombing.

It was in this seemingly inauspicious context that a number of first-rate artists were able to launch their careers having arrived at a renewed sense of creative freedom in the wake of war. Chief among them were Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, and a little later, David Hockney. A masterpiece by each artist will be offered in Visionary: The Paul G. Allen Collection at Christie’s in New York on 9 November.

Throughout their lengthy careers, all three artists defied

prevailing trends and shared a devotion to the figurative, in a period when

abstract art was en vogue.

Freud's Large Interior, W11 (after Watteau) is a

ground-breaking group portrait from the early 1980s. Spanning almost two metres

in both height and width, it was — at the time of its creation — the artist’s

largest painting, as well as his first to feature more than two sitters.

It depicts, from left to right, Celia Paul, his then-lover; Bella,

his daughter; Kai, the son of his former partner, Suzy Boyt; and Suzy Boyt

herself. All four sit huddled together on a bedstead in the upper floor room of

Freud’s West London studio. Lying on the floor in front of them is Star, the

little sister of the then-girlfriend of Ali Boyt (Suzy and Lucian’s son).

It might be tempting to view Large Interior, W11 (after

Watteau) as a snapshot of the artist’s notoriously convoluted personal

life. As the title suggests, however, it was first and foremost a response to

an Old Master painting: namely, Jean Antoine Watteau’s Pierrot content, from 1712 (today found in the Museo

Nacional Thyssen- Bornemisza in Madrid). Freud transposed the Frenchman’s fête

galante, set in an enchanting sylvan glade, to the stark interior of his

studio.

Every detail in it is the product of the artist’s typically

piercing and probing gaze. Pipework is exposed; plaster is bare. Watteau’s

woodland bench becomes an iron bedstead, acquired by Freud for £7 at a recent

house sale. The fountain in the original painting becomes a running tap; the

trees become an unruly indoor plant.

The result, according to the late art historian, Robert Hughes, is

‘a veritable manifesto of Freud’s deeper intentions: to assert the advantages

of scrutiny over theatre’.

Freud was never one for conventional prettiness. He seemed almost

to revel in the unsightly, when he was confronted by it.

He was also renowned for his visceral love of oil paint, something

commonly attributed to the influence, relatively early in his career, of his

friend Francis Bacon. The surface of the Bacon painting being offered — Three

Studies for Self-Portrait, from 1979 — is characteristically thick

with tactile impasto.

The work is a self-portrait triptych, consisting of three close-up

views of the artist’s head, captured at different angles. The spectral pallor

of his flesh is offset by disquieting patches of pink and blue, and set against

a backdrop of blazing orange.

Unlike Freud — who laboured over his portraits for weeks and

sometimes months on end, with an unflinchingly close look at his subjects and

settings — Bacon painted with urgency and high emotion.

Tellingly, he became a septuagenarian in the year that he

created Three Studies for Self-Portrait. The years before it

had seen the deaths of several people close to him (most painfully, his lover

and muse, George Dyer, in 1971, on the eve of a major Bacon retrospective at

the Grand Palais in Paris).

It’s surely no coincidence that, of the 53 named self-portraits in

Bacon’s oeuvre, 29 were painted in the 1970s (only seven of which were

triptychs). As he told the art critic David Sylvester, halfway through that

decade, ‘I’ve done a lot of self-portraits, really because people have been

dying around me like flies, and I’ve had nobody else left to paint but myself’.

The present work can be considered part of that outpouring.

With the possible exception of Rembrandt, it’s hard to think of an

artist who has ever been quite so frank and artistically daring in the name of

self-observation.

Bacon famously turned to photographs instead of painting from life,

to ‘distort the thing far beyond the appearance, but in the distortion to bring

it back to a recording of the appearance’. For his self-portraits, Bacon also

turned to the mirror, where he would study his own face letting his

stubble grow for several days and using pots of Max Factor theater make-up to

practise swirls and distortions upon his features.

David Hockney is a different artist

altogether. His imagery has always been much more upbeat than Bacon and Freud’s

was: tending to be vibrantly colourful and angst-free.

The Conversation, from 1980, is one of the Yorkshireman’s

famed double portraits, a type of picture in which he examines the relationship

between a pair of friends and relatives. Hockney’s fondness for these works

stemmed from his belief that portraiture need not be defined solely by the

connection between subject and painter — but by the connection between subjects

too.

The Conversation depicts two of the artist’s friends — the

eminent American curator Henry Geldzahler, and his partner, the

twenty-something publisher Raymond Foye — sitting down together, amid what

looks like a strained discussion. The former leans forward, seemingly just

finishing a point, his right arm resting on his crossed left leg. The latter is

slunk slightly back in his chair, listening, somewhat unimpressed and appearing

to be contemplating his response.

Such is Hockney’s talent as a painter that the flow of conversation

is almost palpable, even without our being able to hear a word.

Unlike his previous double portraits — which commonly were set in

elaborate domestic surroundings that provide an insight into the relationship

explored — the scene in The Conversation is spare. There’s

just a folding yellow screen behind Geldzahler and Foye. The viewer is left to concentrate on gesture and pose.

Hockney may not have had Freud’s forensic eye

or Bacon’s existential world-view, but his double portraits fizz with

psychological tension.

All three paintings from the collection of

Paul G. Allen were created within a few years of each other, by artists who, at

that stage of their careers, had considerable experience to go with their

considerable skill.

It’s true that they weren’t exactly the same

age (Bacon was more than a decade older than Freud, who in turn was more than a

decade older than Hockney). However, according to fellow-painter, Frank

Auerbach, they had one crucial thing in common: ‘a curious feeling of liberty’

after having lived through the horrors of the Second World War.

That liberty manifested itself in a trio who, though working figuratively, all arrived at very distinct ways of painting and seeing.

https://www.christies.com/features/visionaries-of-portrait-bacon-freud-hockney-12459-3.aspx?sc_lang=en&cid=EM_EMLcontent04144C22Section_A_Story_1_0&COSID=42665747&cid=DM483367&bid=327203832#fid-12459

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario