On 25 November 1915 Albert Einstein announced to members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin that his general theory of relativity was complete. It encompasses some of the most important ideas in modern physics, expanding the special theory of relativity he published in 1905.

The earlier theory includes his famous equation E = mc2, which

quantifies the relationship between the mass of an object and its energy, while the

general theory updates and refines the universal theory of gravitation developed

by Isaac Newton in the 17th century.

Both relativistic theories assume that the

three dimensions of physical space are inextricably intertwined with a fourth – time. It is distortions of four-dimensional ‘spacetime’ that produce gravity, which in turn

determines the size and shape of the universe.

On 23 November, nearly 106 years to the day

that Einstein forever changed the way we understand the cosmos, Christie’s

France and auction house Aguttes will present an extremely rare monograph that

played a crucial role in the development of general relativity.

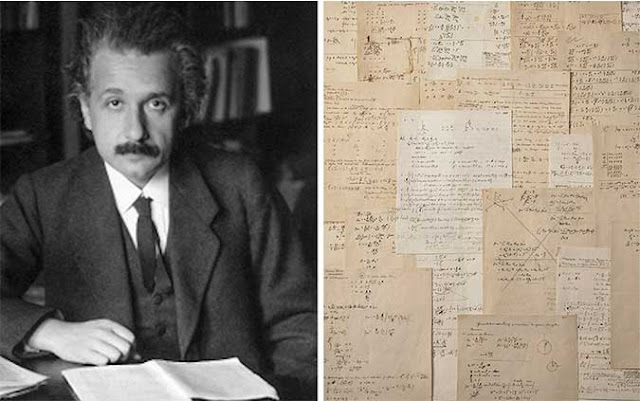

Known as the Einstein-Besso Manuscript, the

54-page document was written between June 1913 and early 1914 by Einstein and

his lifelong friend and colleague, the Swiss-Italian engineer Michele Besso,

who the physicist had known since they were both students. It includes

equations that led Einstein to paint his radical new picture of the universe.

Apart from a manuscript held at the Albert

Einstein Archives at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, the Einstein-Besso

Manuscript is the only surviving work detailing the genesis of general

relativity. Featuring 26 pages in Einstein’s hand and 25 in Besso’s, with three

pages of entries by both, the manuscript attempts to explain an anomaly in Mercury’s orbit using versions of the equations Einstein

would use to prove his theory of general relativity.

The two men sought to confirm that Mercury’s

perihelion, the point where the planet is closest to the Sun, changes slowly

over time because of the curvature of spacetime. However, both scientists made

a couple of mistakes in the manuscript, and Einstein later on realised that the

equations were not quite the right ones yet. He would then correct his findings

independently later.

Einstein was not one to save early drafts of his work — hence there are few autographed manuscripts from this momentous point in his career — but Besso kept the document safely in his home until his death in 1955, which accounts for its impeccable condition.

‘The manuscript isn’t bound, and there are

many different types of loose paper, so you get the impression of a working

document that’s full of energy, as if both men would grab the first page they

could find to scribble their findings on,’ says Vincent Belloy, specialist in

the Books & Manuscripts department at Christie’s Paris. ‘The size of each

leaf is generally the same [273 x 212mm] and the pages were arranged in the right

order when it was first revealed by the Besso estate in the early 1990s. Of

course, it’s not clear if Michele Besso took the manuscript or if Einstein sent

it to him, asking him to work through their findings.’

What is certain is that the men had very different

methods, as demonstrated by their handwriting styles and how they presented

information. ‘What’s interesting is the sense of personality that comes across

in these pages,’ says Belloy. ‘You get the impression that Einstein was perhaps

more confident in his calculations since his sheets are much lighter in terms

of textual content and reserved almost exclusively for calculations. Besso, by

contrast, often added written notes in the margin.’

https://www.christies.com/features/cosmically-significant-11961-1.aspx?sc_lang=en&cid=EM_EMLcontent04144B86Section_A_Story_4_0&COSID=42665747&cid=DM468789&bid=289417366#fid-11961

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario